Call vs. Puts: Understand the Different Types of Options

When you’re new to options trading, it can feel overwhelming trying to figure out what to learn and in what order. But one of the first things you’ll need to understand is the difference between calls vs. puts. These are fundamental.

If you’re new to these foundational terms, then you’re in the right place!

This is part of our Options 101 series, where we teach you everything you need to know to get started in the options world.

In this guide, we’ll break down calls and puts in a way that’s simple, practical, and easy to remember.

You’ll learn what they are, how they work, and when traders typically use each one — without getting lost in jargon.

By the end, you’ll have a clear understanding of the building blocks of options trading, bringing you one step closer to trading with confidence.

Now let’s dive in!

Table of Contents

What Are Calls vs. Puts?

Here’s the first thing to know about options trading: all options contracts are either a call option or a put option. Here’s what that means:

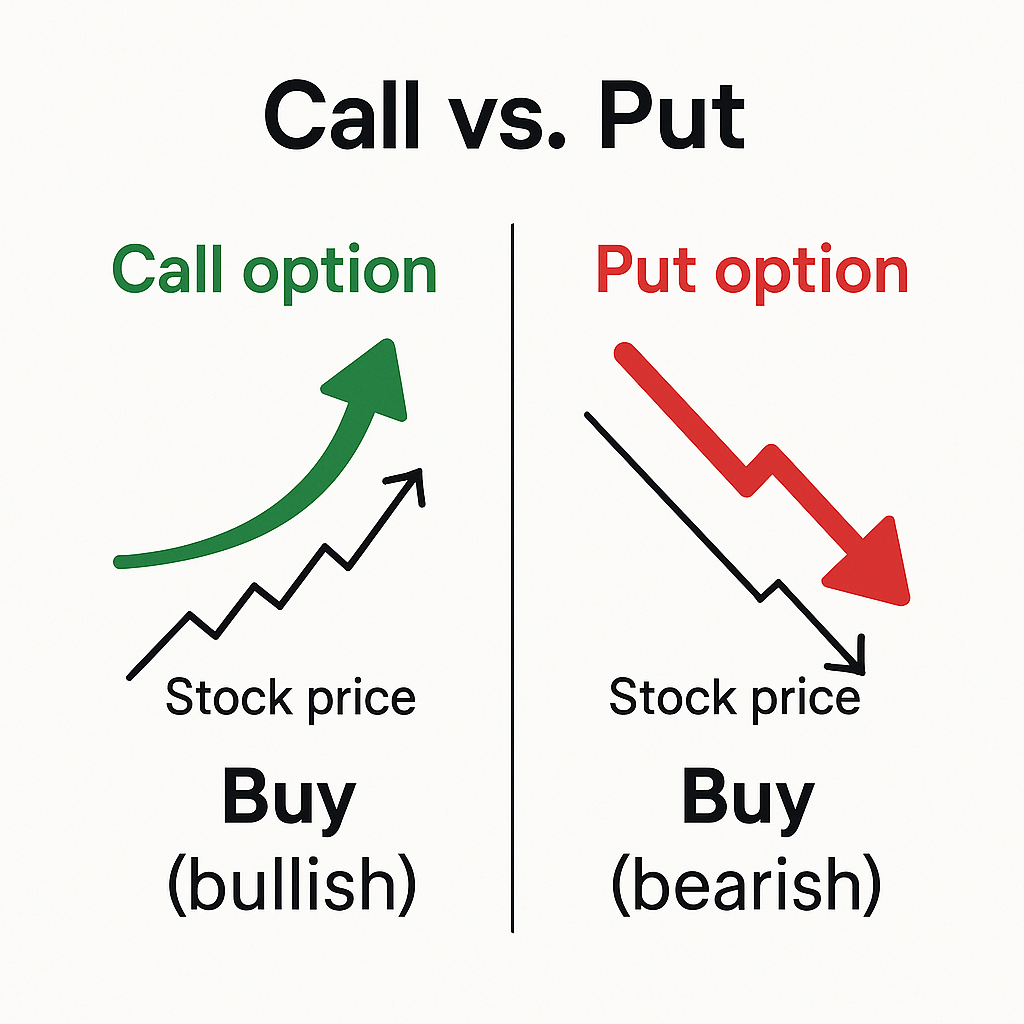

A Call Option Is a Right to Buy

A call gives the buyer the right (but not obligation) to buy the underlying asset at the strike price before the option expires.

If you buy a call, you’re hoping the stock’s price goes up. Then you could either exercise the option to buy the stock at the cheaper strike price or sell the option contract itself for a profit.

For example, let’s say you have a call option to buy a stock at $50 and the stock rises to $60, then your call is valuable (it lets you buy at $50 when everyone else has to pay $60).

A Put Option Is a Right to Sell

A put is the opposite of a call. It gives the buyer the right (but not obligation) to sell the underlying asset at the strike price before expiration.

If you buy a put, you’re hoping the stock’s price goes down. The put becomes valuable if the stock falls below the strike price (because it lets you sell at a higher-than-market price).

For example, a put option to sell a stock at $50 is valuable if the stock’s market price drops to $40 (aka, you have the right to sell at $50 when others can only get $40).

Call or put, the option buyer can choose to exercise the option or simply sell the option contract to someone else before it expires. In practice, many options traders don’t actually exercise their options; instead, they trade the option itself to take profits or cut losses.

What Happens When You Sell Options? Option Sellers 101

So what about the option seller? The seller (writer) of an option takes on an obligation:

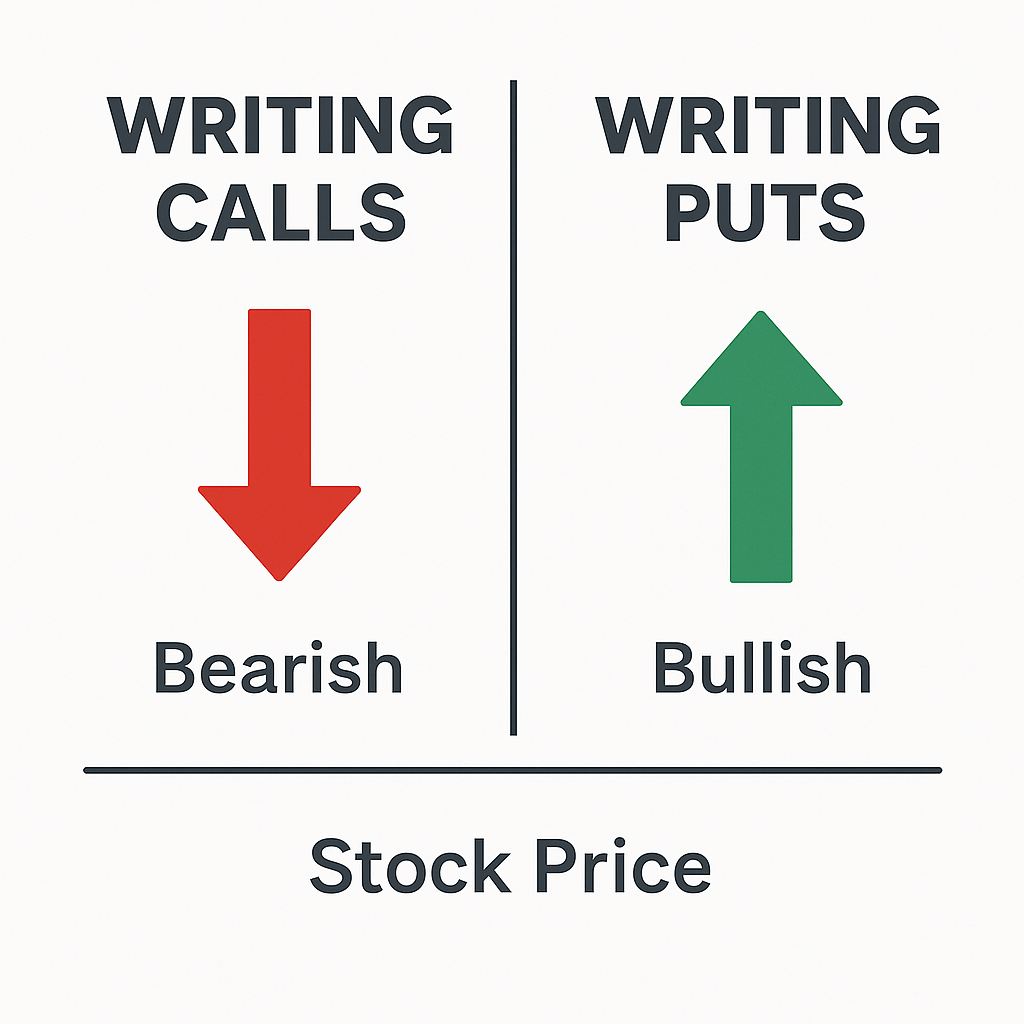

1. Selling a call option

If you sell a call option, you are obligated to sell the stock at the strike price if the buyer exercises the option. Call sellers are generally bearish and want the stock price to stay below the strike, so the call expires worthless (letting the seller keep the premium without having to sell shares).

2. Selling a put option

If you sell a put option, you are obligated to buy the stock at the strike price if the buyer exercises. Put sellers are generally bullish and want the stock price to stay above the strike, so the put expires worthless (the seller keeps the premium without having to buy shares).

As a beginner, it’s usually recommended to start with buying options (calls or puts) rather than selling them. Buying options has limited risk – you can only lose the premium you paid. Selling options, especially without owning the underlying stock (called “naked” selling), can have much larger risk if the market moves against you.

Now, we have one more piece of jargon you might hear: “in the money,” “at the money,” or “out of the money”.

Key Concepts to Know When Trading Options

Before you start trading options (and making money), it’s important to learn some more concepts. Let’s explore these ideas.

In the Money, Out of the Money & At the Money

In the money (ITM), out of the money (OTM), and at the money (ATM) – these terms describe the relationship between the stock price and the option’s strike.

An ITM option can be exercised for an immediate profit (ignoring the premium cost), while an OTM option would currently be worthless to exercise (though it could still have time value if there’s a chance of moving ITM before expiration).

In the Money (ITM)

The option already has intrinsic value. For a call, ITM means the stock price is above the strike price. For a put, ITM means the stock price is below the strike.

Out of the Money (OTM)

The option has no intrinsic value yet. For a call, OTM means the stock is below the strike (not high enough); for a put, OTM means the stock is above the strike (not low enough).

At the Money (ATM)

The stock price is roughly equal to the strike price.

Implied Volatility (IV)

When you trade options, it’s not just about where a stock’s price is — it’s about how much the market thinks it might move. That’s where Implied Volatility (IV) comes in.

IV measures the market’s expectations for how much a stock could move in the future.

It doesn’t predict which direction — just how volatile traders think the stock will be.

Think of IV like a “mood ring” for the market:

- Big moves expected = IV goes up

- Calm expected = IV goes down

Here’s why it matters:

Higher IV means you’re paying more for the “potential” of a big move. Lower IV means options are cheaper.

Pro Tip:

- High IV = Expensive options

- Low IV = Cheaper options

- Rising IV = Good for option buyers

- Falling IV = Good for option sellers

Later, you’ll learn about things like “IV crush” (a common beginner trap) — but for now, just remember:

IV impacts option prices, even if the stock hasn’t moved yet.

What Happens at Expiration?

When you trade options, every contract comes with an expiration date. And understanding what happens at expiration is key to managing your trades smartly.

Here’s a simple breakdown of what happens to an option at expiration:

- If your option is in the money (ITM) when it expires, your broker might automatically exercise it for you.

- If you owned a call option, you could end up buying the stock at the strike price

- If you owned a put option, you could end up selling the stock at the strike price

- If your option is out of the money (OTM) when it expires, it simply expired worthless

- You don’t owe anything extra, but you do lose the premium you paid

But note that most traders don’t wait until expiration day to act.

Instead, they usually choose to sell the option before expiration — either to lock in a profit or limit a loss.

👉 Pro Tip: Always know your plan before expiration sneaks up on you. Whether you want to sell, exercise, or let the option expire, having a game plan keeps you in control.

Ready to Start Trading Options?

Now you’ve mastered the basics of calls and puts — the foundation of the entire options world. You learned:

- What calls vs. puts actually mean

- Why “in the money,” “out of the money,” and “at the money” matter

- How implied volatility (IV) affects option pricing

- What to expect when your options reach expiration

Options trading might seem complicated at first, but once you break it down piece by piece, it becomes a powerful tool to manage risk, generate income, and trade with flexibility.

And if you’re ready to keep learning more, then check out our free options calculators! These are perfect to better understand your profit potential and learn about other key options metrics.